Vasily Aksyonov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

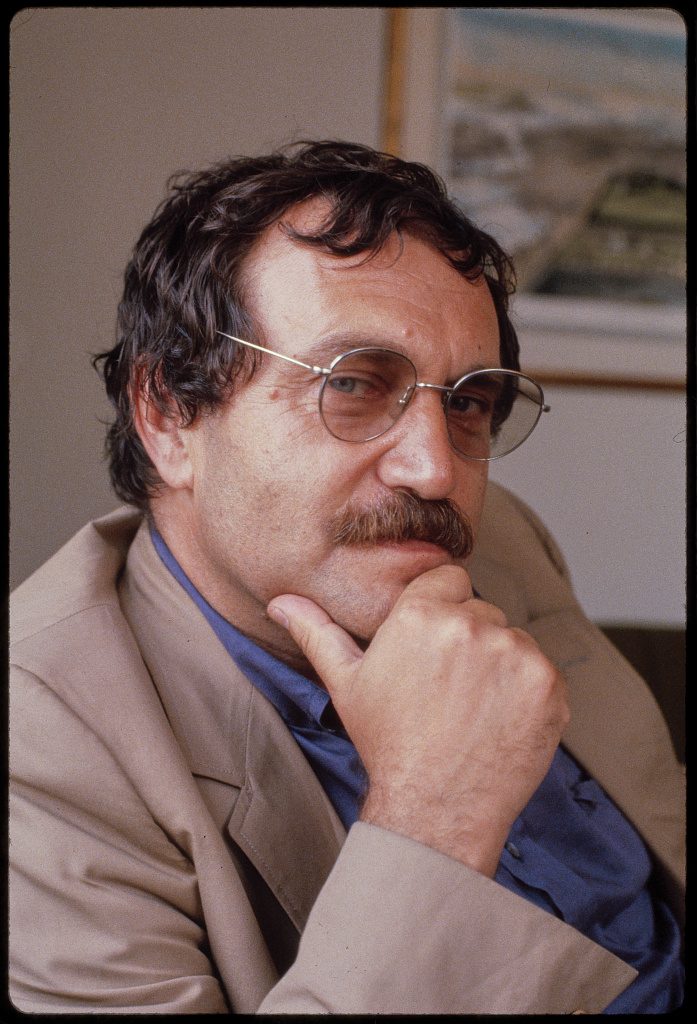

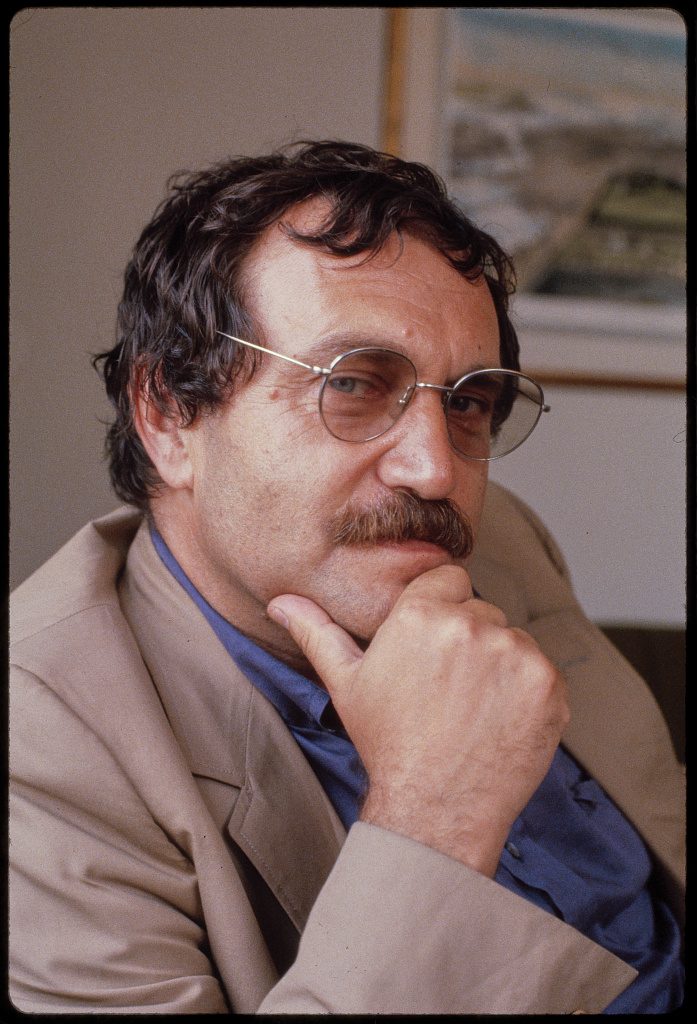

Vasily Pavlovich Aksyonov ( rus, Васи́лий Па́влович Аксёнов, p=vɐˈsʲilʲɪj ˈpavləvʲɪtɕ ɐˈksʲɵnəf; August 20, 1932 – July 6, 2009) was a

Reportedly, "during the liberalisation that followed Stalin's death in 1953, Aksyonov came into contact with the first Soviet countercultural movement of zoot-suited hipsters called '' stilyagi'' (the ones 'with style')." As a result,

Reportedly, "during the liberalisation that followed Stalin's death in 1953, Aksyonov came into contact with the first Soviet countercultural movement of zoot-suited hipsters called '' stilyagi'' (the ones 'with style')." As a result,

''Booknotes'' interview with Aksyonov on ''Say Cheese'', November 5, 1989.''Metropol Madness''

Documents related to the journal Metropol, edited by Aksyonov. *

{{DEFAULTSORT:Aksyonov, Vassily Soviet dissidents Writers from Kazan Soviet emigrants to the United States Jewish Russian writers Russian male novelists Russian medical writers Soviet novelists Soviet male writers 20th-century Russian male writers Soviet short story writers 20th-century Russian short story writers Russian alternate history writers Honorary Members of the Russian Academy of Arts 1932 births 2009 deaths Russian Booker Prize winners University of Southern California faculty Goucher College faculty and staff Russian-language writers Russian male short story writers People denaturalized by the Soviet Union Burials at Vagankovo Cemetery

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

novelist

A novelist is an author or writer of novels, though often novelists also write in other genres of both fiction and non-fiction. Some novelists are professional novelists, thus make a living writing novels and other fiction, while others aspire to ...

. He became known in the West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sunset, Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic languages, German ...

as the author of ''The Burn'' (''Ожог'', ''Ozhog'', from 1975) and of '' Generations of Winter'' (''Московская сага'', ''Moskovskaya Saga'', from 1992), a family saga

The family saga is a genre of literature which chronicles the lives and doings of a family or a number of related or interconnected families over a period of time. In novels (or sometimes sequences of novels) with a serious intent, this is often ...

following three generations of the Gradov family between 1925 and 1953.

Early life

Vasily Aksyonov was born to Pavel Aksyonov andYevgenia Ginzburg

Yevgenia Solomonovna Ginzburg (December 20, 1904 – May 25, 1977) (russian: Евге́ния Соломо́новна Ги́нзбург) was a Soviet writer who served an 18-year sentence in the Gulag. Her given name is often Latinized to Eugenia ...

in Kazan

Kazan ( ; rus, Казань, p=kɐˈzanʲ; tt-Cyrl, Казан, ''Qazan'', IPA: ɑzan is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and the Kazanka rivers, covering a ...

, USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

on August 20, 1932. His mother, Yevgenia Ginzburg, was a successful journalist and educator and his father, Pavel Aksyonov, had a high position in the administration of Kazan. Both parents "were prominent communists." In 1937, however, both were arrested and tried for her alleged connection to Trotskyists

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a re ...

. They were both sent to Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

and then to exile, and "each served 18 years, but remarkably survived." "Later, Yevgenia came to prominence as the author of a famous memoir, ''Into the Whirlwind'', documenting the brutality of Stalinist repression."

Aksyonov remained in Kazan with his nanny and grandmother until the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

arrested him as a son of "enemies of the people

The term enemy of the people or enemy of the nation, is a designation for the political or class opponents of the subgroup in power within a larger group. The term implies that by opposing the ruling subgroup, the "enemies" in question are ac ...

", and sent him to an orphanage without providing his family any information on his whereabouts. Aksyonov "remained here

Here is an adverb that means "in, on, or at this place". It may also refer to:

Software

* Here Technologies, a mapping company

* Here WeGo (formerly Here Maps), a mobile app and map website by Here Technologies, Here

Television

* Here TV (form ...

until rescued in 1938 by his uncle, with whose family he stayed until his mother was released into exile, having served 10 years of forced labour." "In 1947, Vasily joined her in exile in the notorious Magadan

Magadan ( rus, Магадан, p=məɡɐˈdan) is a port town and the administrative center of Magadan Oblast, Russia, located on the Sea of Okhotsk in Nagayev Bay (within Taui Bay) and serving as a gateway to the Kolyma region.

History

Maga ...

, Kolyma

Kolyma (russian: Колыма́, ) is a region located in the Russian Far East. It is bounded to the north by the East Siberian Sea and the Arctic Ocean, and by the Sea of Okhotsk to the south. The region gets its name from the Kolyma River an ...

prison area, where he graduated from high school." Vasily's half-brother Alexei (from Ginzburg's first marriage to Dmitriy Fedorov) died from starvation in besieged Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

in 1941.

His parents, seeing that doctors had the best chance to survive in the camps, decided that Aksyonov should go into the medical profession. "He therefore entered the Kazan University

Kazan (Volga region) Federal University (russian: Казанский (Приволжский) федеральный университет, tt-Cyrl, Казан (Идел буе) федераль университеты) is a public research uni ...

and graduated in 1956 from the First Pavlov State Medical University of St. Peterburg" and worked as a doctor for the next 3 years. During his time as a medical student he came under surveillance by the KGB, who began to prepare a file against him. It is likely that he would have been arrested had the liberalisation that followed Stalin's death in 1953 not intervened.

Career

Reportedly, "during the liberalisation that followed Stalin's death in 1953, Aksyonov came into contact with the first Soviet countercultural movement of zoot-suited hipsters called '' stilyagi'' (the ones 'with style')." As a result,

Reportedly, "during the liberalisation that followed Stalin's death in 1953, Aksyonov came into contact with the first Soviet countercultural movement of zoot-suited hipsters called '' stilyagi'' (the ones 'with style')." As a result,

He fell in love with their slang, fashions, libertine lifestyles, dancing and especially their music. From this point on began his lifelong romance with jazz. Interest in his new milieu, western music, fashion and literature turned out to be life-changing for Aksyonov, who decided to dedicate himself to chronicling his times through literature. He remained a keen observer of youth, with its ever-changing styles, movements and trends. Like no other Soviet writer, he was attuned to the developments and changes in popular culture.In 1956, he was "discovered" and heralded by the Soviet writer

Valentin Kataev

Valentin Petrovich Kataev (russian: Валенти́н Петро́вич Ката́ев; also spelled Katayev or Kataiev; – 12 April 1986) was a Russian and Soviet novelist and playwright who managed to create penetrating works discussing ...

for his first publication, in the liberal magazine Youth. "His first novel, ''Colleagues'' (1961), was based on his experiences as a doctor." "His second, ''Ticket to the Stars'' (1961), depicting the life of Soviet youthful hipsters, made him an overnight celebrity."

In the 1960s Aksyonov was a frequent contributor to the popular ''Yunost

''Yunost'' (russian: Ю́ность, ''Youth'') is a Russian language literary magazine created in 1955 in Moscow (initially as a USSR Union of Writers' organ) by Valentin Kataev, its first editor-in-chief, who was fired in 1961 for publishing Va ...

'' ("Youth") magazine and eventually became a staff writer. Aksyonov thus reportedly became "a leading figure in the so-called "youth prose" movement and a darling of the Soviet liberal intelligentsia and their western supporters: his writings stood in marked contrast to the dreary, socialist-realist prose of the time."''Obituary: Vasily Aksyonov: Libertarian Russian writer and leading light in 'youth prose', he fell foul of the KGB.'' Mark Yoffe. The Guardian (London) – Final Edition July 16, 2009. GUARDIAN OBITUARIES PAGES; pg. 34. "Aksyonov's characters spoke in a natural way, using hip lingo, they went to bars and dance halls, had premarital sex, listened to jazz and rock'n'roll and hustled to score a pair of cool American shoes." "There was a feeling of freshness and freedom about his writings, similar to the one emanating from black-market recordings of American jazz and pop." "He soon became one of the informal leaders of the Shestidesyatniki – which translates roughly as "the '60s generation" – a group of young Soviets who resisted the Communist Party's cultural and ideological restrictions." "'It was amazing: We were being brought up robots, but we began to listen to jazz,' Aksyonov said in a 2007 documentary about him."

For all his hardship, Aksyonov,

as a prose stylist, was at the opposite pole from Mr.However, as Mark Yoffe notes in Aksyonov's obituary, his "open pro-Americanism and liberal values eventually led to problems with the KGB." "And his involvement in 1979 with an independent magazine, ''Metropol'', led to an open confrontation with the authorities." His next two celebrated dissident novels, ''The Burn'' and ''The Island of Crimea'', could not be published in the USSR. "The former explored the plight of intellectuals under communism and the latter was an imagining of what life might have been like had theSolzhenitsyn Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian novelist. One of the most famous Soviet dissidents, Solzhenitsyn was an outspoken critic of communism and helped to raise global awareness of political repress ..., becoming a symbol of youthful promise and embracing fashion and jazz rather than dwelling on the miseries of the gulag. Ultimately, however, he shared Mr. Solzhenitsyn's fate of exile from the Soviet Union. ''Solzhenitsyn is all about the imprisonment and trying to get out, and Aksyonov is the young person whose mother got out and he actually can live his life now,'' said Nina L. Khrushcheva, who is a granddaughter ofNikita Khrushchev Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...and a friend of the Aksyonov family and who teaches international affairs at the New School in New York. ''It was important to have the Aksyonov light, that light of personal freedom and personal self-expression.''

white army

The White Army (russian: Белая армия, Belaya armiya) or White Guard (russian: Бѣлая гвардія/Белая гвардия, Belaya gvardiya, label=none), also referred to as the Whites or White Guardsmen (russian: Бѣлогв� ...

staved off the Bolsheviks in 1917."

"When ''The Burn'' was published in Italy in 1980, Aksyonov accepted an invitation for him and his wife Maya to leave Russia for the US." "Soon afterwards, he was stripped of his Soviet citizenship, regaining it only 10 years later during Gorbachev's perestroika."

"Aksyonov spent the next 24 years in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

and Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, where he taught Russian Literature

Russian literature refers to the literature of Russia and its émigrés and to Russian language, Russian-language literature. The roots of Russian literature can be traced to the Middle Ages, when epics and chronicles in Old East Slavic were c ...

at George Mason University

George Mason University (George Mason, Mason, or GMU) is a public research university in Fairfax County, Virginia with an independent City of Fairfax, Virginia postal address in the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Area. The university was origin ...

."''Vasily Aksyonov, 76, Exiled Soviet Writer.'' SOPHIA KISHKOVSKY. The New York Times July 8, 2009. Section A; Column 0; Obituary; pg. 23. "He lsotaught literature at a number of ther Ther may refer to:

*''Thér.'', taxonomic author abbreviation of Irénée Thériot (1859–1947), French bryologist

* Agroha Mound, archaeological site in Agroha, Hisar district, India

*Therapy

*Therapeutic drugs

See also

*''Ther Thiruvizha

''T ...

American universities, including USC

USC most often refers to:

* University of South Carolina, a public research university

** University of South Carolina System, the main university and its satellite campuses

**South Carolina Gamecocks, the school athletic program

* University of ...

and Goucher College

Goucher College ( ') is a private liberal arts college in Towson, Maryland. It was chartered in 1885 by a conference in Baltimore led by namesake John F. Goucher and local leaders of the Methodist Episcopal Church.https://archive.org/details/h ...

in Maryland... ndworked as a journalist for Radio Liberty."OBITUARIES / VASILY AKSYONOV, 1932 – 2009; Dissident writer was expelled from the Soviet Union Los Angeles Times July 10, 2009. MAIN NEWS; Metro Desk; Part A; Pg. 26.

"He continued to write novels, among which was the ambitious ''Generations of Winter'' (1994), a multi-generational saga of Soviet life that became a successful Russian TV mini-series." The so-called "''The Moscow Saga,'' his 1994epic trilogy... described the lives of three generations of a Soviet family between the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution and Stalin's death in 1953." The TV mini-series consisted of 24 episodes and was broadcast on Russian television in 2004. " n 1994 he also won the Russian Booker Prize, Russia's top literary award, for his historical novel ''Voltairian Men and Women,'' about a meeting between the famous philosopher Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

and Empress Catherine II

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anha ...

."

"In 2004, he settled in Biarritz, France

Biarritz ( , , , ; Basque also ; oc, Biàrritz ) is a city on the Bay of Biscay, on the Atlantic coast in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department in the French Basque Country in southwestern France. It is located from the border with Spain ...

, and returned to the US less frequently, dividing his time between France and Moscow." His novel ''Moskva-kva-kva'' (2006) was published in the Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

-based magazine ''Oktyabr''.

"Aksyonov was translated into numerous languages, and in Russia remained influential". In addition to writing novels, he is also known as author of poems, occasionally performed as songs. He was reportedly "forever a hipster ndwas used to being in the avant garde, be it in fashion or literary innovation." He was described as "a colourful man, with his trademark moustache, elegant suits, expensive cars, and a love for grand cities, fine wine and good food."

On July 6, 2009, he died in Moscow at the age of 76.

Political views

Vasily Aksyonov was a convinced anti-totalitarian. On the presentation of one of his last novels, he stated: "If in this country one starts erecting Stalin statues again, I have to reject my native land. Nothing else remains."Novels

His other novels include: * ''Colleagues'' ("Коллеги" – ''Kollegi'', 1960) * ''Ticket to the Stars'' ("Звёздный билет" – ''Zvyozdny bilet'', 1961) * ''Oranges from Morocco'' ("Апельсины из Марокко" – ''Apel'siny iz Marokko'', 1963) * ''It's Time, My Friend, It's Time'' ("Пора, мой друг, пора" – ''Pora, moy drug, pora'', 1964) * ''It's a Pity You Weren't with Us'' ("Жаль, что вас не было с нами" – ''Zhal', chto vas ne bylo s nami'', 1965) * "Half-way To The Moon" ("На полпути к Луне", 1966) * ''Overstocked Packaging Barrels'' ("Затоваренная бочкотара" – ''Zatovarennaya bochkotara'', 1968) * "My Grandfather Is A Monument" ("Мой дедушка — памятник", 1970) * "Love for Electricity" ("Любовь к электричеству", 1971) * ''In Search of a Genre'' ("В поисках жанра" – ''V poiskakh zhanra'', 1972) * "Our Golden Piece Of Metal ("Золотая наша Железка", 1973) * "The Burn" ("Ожог", 1975) * Translation ofE.L. Doctorow

Edgar Lawrence Doctorow (January 6, 1931 – July 21, 2015) was an American novelist, editor, and professor, best known for his works of historical fiction.

He wrote twelve novels, three volumes of short fiction and a stage drama. They included ...

's ''Ragtime'' into Russian (1976)

* ''The Island of Crimea'' ("Остров Крым" – "Ostrov Krym", 1979)

* "The Steel Bird and Other Stories" ("Стальная Птица и Другие Рассказы", 1979)

* "Paper Landscape" ("Бумажный пейзаж", 1982)

* ''Say Cheese'' ("Скажи изюм" – ''Skazhi izyum'', 1983)

* ''In Search of Melancholy Baby'' ("В поисках грустного бэби" – ''V poiskakh grustnogo bebi'', 1987)

* ''Yolk of the Egg'' (written in English, author's translate in Russian — "Желток яйца" — ''Zheltok yaytsa'', 1989)

* '' Generations of Winter'' (English ed. of "Московская сага", 1994). Random House. .

* ''The New Sweet Style'' ("Новый сладостный стиль" – ''Novy sladostny stil, 1998)

* "Cesarean" ("Кесарево свечение", 2000)

* ''Voltairian Men and Women'' ("Вольтерьянцы и вольтерьянки" – ''Volteryantsy i volteryanki'', 2004 – won the Russian Booker Prize

The Russian Booker Prize (russian: Русский Букер, ''Russian Booker'') was a Russian literary award modeled after the Booker Prize. It was awarded from 1992 to 2017. It was inaugurated by English Chief Executive Sir Michael Harris C ...

).

* ''Moscow ow ow'' ("Москва Ква-Ква" – ''Moskva Kva-Kva'', 2006)

* ''Rare Earths'' ("Редкие земли" – ''Redkie zemli'', 2007)

Theatre

* ''Colleagues'' 1959 * ''Always In Sale'' 1965 * ''Duel'' 1969 * ''The Four Temperaments'' published in the Literary Almanac "Metropol", New York and London 1979,Literature

* "The Poet Vasily Aksyonov" essay 1980 and thesis ofHerbert Gantschacher

Herbert Gantschacher (born December 2, 1956, at Waiern in Feldkirchen in Kärnten, Carinthia, Austria) is an Austrian director and producer and writer.

Education

1976 Gantschacher graduated on the second school in Klagenfurt. From 1977 to 19 ...

for obtaining the academic title "Master of Arts" at the Academy, today University of Music and Performing Arts, Graz, Re / 1653/1988, July 1988

* "A Life 'In A Burning Skin'" essay by Jürgen Serke in "The Banned Poets", Hamburg 1982,

References

External links

*''Booknotes'' interview with Aksyonov on ''Say Cheese'', November 5, 1989.

Documents related to the journal Metropol, edited by Aksyonov. *

{{DEFAULTSORT:Aksyonov, Vassily Soviet dissidents Writers from Kazan Soviet emigrants to the United States Jewish Russian writers Russian male novelists Russian medical writers Soviet novelists Soviet male writers 20th-century Russian male writers Soviet short story writers 20th-century Russian short story writers Russian alternate history writers Honorary Members of the Russian Academy of Arts 1932 births 2009 deaths Russian Booker Prize winners University of Southern California faculty Goucher College faculty and staff Russian-language writers Russian male short story writers People denaturalized by the Soviet Union Burials at Vagankovo Cemetery